Director Erik Rojas talks creativity in film, working with Waterparks and more

Each issue, AP Gallery explores the visual culture of music and highlights the stories behind iconic music videos and the inspiration for the most memorable photographs.

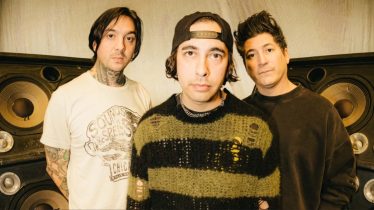

For Issue 394 featuring Waterparks on the cover, we connected with Erik Rojas, a Colombian-American music video director known for visually capturing the essence of a song. After finishing a degree at Boston University, Rojas relocated to L.A. and landed a position with the prestigious studio A52/Rock Paper Scissors. From there, he quickly established a place for himself in the industry, working as a cinematographer, director and creative talent. As a music video director, Rojas has already worked with an impressive list of artists, including American Teeth, DE’WAYNE, Waterparks, Isaac Dunbar, Halo Boy, Jessie J and more.

Read more: FINNEAS leads blòkur’s Top 5 Songwriters On Spotify list for 2020

View this post on Instagram

Rojas spoke to Alternative Press about his career and some of his most interesting projects. He told us about his unique path into directing and his goal of creating an inviting, social atmosphere on set. Rojas took us behind the scenes of Chase Atlantic’s “HEAVEN AND BACK,” Waterparks’ “NOT WARRIORS/CRYBABY” and Halo Boy’s “Fame.” He also recalled the time he let Herizen Guardiola spray-paint his car to craft the perfect visual for “Troublemaker.”

Your journey into film is unique. How did you end up working in the industry, and what led you to music videos in particular?

I grew up in a small inner city-type place in Massachusetts called Lowell. My dad’s an immigrant from Colombia, and my mom’s from Massachusetts. I messed around with a MiniDV camera that I got for my birthday when I was 16, but I never really saw something that was creative as a career. My mentality was like, “I have to figure out how to sustain myself.”

I didn’t actually go to Boston [University] with the intent of studying film. It wasn’t until the second half of freshman year that a really good friend of mine who I met at BU, Steph Mirsky, was like, “Hey, I write this music blog. I can get you a photo pass to take pictures.” At the time, dubstep was really big. Rusko was coming through Boston to play a show, and I was like, “Dude, do you think I could get a press pass to go cover the show and basically just watch it?” We both went to the Rusko show. I’m like, “Fuck, I don’t know what to do.” He’s like, “Just put it on auto and go in the pit.” There was something really mystical at that moment, just looking through the viewfinder, capturing something and seeing what it looked like on the screen. So I saved up a bunch of money and ended up buying my own camera within the next six months.

Read more: AltPress Weekly: Badflower, Yvette Young, industry insiders and more

[By] sophomore year, I signed up to be a film/communication minor-major. Every single waking moment I had, I was teaching myself. I got Premiere and Photoshop and started taking photos and videos. As soon as I graduated, I was able to move out [to Los Angeles]. I worked a 4 p.m. to 4 a.m. shift for a year-and-a-half. I was able to get connected with one of the Hughes brothers, who did Menace II Society and The Book Of Eli. Albert Hughes took me onto his first solo feature film that he was directing [Alpha], all across Canada and Iceland. It was serendipitous because I was 23 and just starting to realize that I didn’t want to work in post-production. I actually wanted to be a director. So I went on a crash course [with] this legendary guy, learned all this filmmaking, storytelling ability and stuff.

As soon as that film ran its course, I fully dove into being a freelance director. It was right around the time that I met DE’WAYNE. We did some videos together, and that led to the Chase Atlantic video for “Triggered.” That was what set the snowball in place. That was two-and-a-half, three years ago. Through working with all those different artists, I started to build a voice and a style. It’s funny how those things feed themselves. More and more people within the music community see that they may or may not want to work with me. And then you just have constant new projects coming up. It’s really cool because, ultimately, you’re being a creative. Even though it’s a job, it doesn’t feel like it.

I wanted to ask you about the video you shot for Chase Atlantic’s “HEAVEN AND BACK.” The visual has a really distinctive atmosphere. Can you tell us about that project?

That was an idea that just came to my head one day while we were chilling in a coffee shop. What I’m realizing is, I like dark colors. I like cyber-feeling stuff like Drive [and] Blade Runner 2049. The overall aesthetic of deep, rich colors is something I unknowingly did a lot. I’ve heard that about the “HEAVEN AND BACK” video a lot, just like the emphasis on the colors [and] specifically the purple, obviously.

I noticed that in a number of your videos, you use bold colors, especially strong single colors that really define a shot. Is that something intentional for you?

With music videos, you have a little bit more [opportunity] to go extreme. I think [Chase Atlantic] were also gravitating toward a purple overall palette. I remember that specific shoot. It was one of the first times I worked with the DP Mike [Koziel], who is now one of my best friends and one of my constant collaborators. We had other colors in the frame, like two blue spotlights.

I was like, “It still doesn’t feel as moody. Let’s just put gel over those and take this huge light called a SkyPanel. Let’s move it over to the side and make it purple and blast the fog machine.” I remember seeing the band and all the extras. I was like, “Whoa, this is it.” Sometimes those spontaneous decisions to go extreme end up making something that’s really memorable. That moment where all the pieces are in play and you can start to roll the music or direct the actors, when the lighting is set and you’ve created a world, there’s a really magical feeling to that. That overall color wash that I’ve done in other videos, I think that as a creative, you just do things that you gravitate toward.

I also wanted to ask you about the video you made for Waterparks, “NOT WARRIORS/CRYBABY.” That’s got to be one of your more unique projects. Can you tell us about that one?

That video was a collaborative effort between myself [and] a director named Joe [Mischo]. Awsten [Knight] wrote the treatment. We got an email, I want to say a 12-page Word document, [and] it was shot for shot. The thing with music videos, especially nowadays, it’s not like the 2000s where it’s like, “Here’s a million dollars. Put Akon in a helicopter [and] fly around the city.” Because of the different musical environment we’re in, you have a certain financial ceiling that you have to get creative to work with.

I remember in the treatment, it was like, “Car set on fire, spray-painting ‘ENTERTAINMENT’ upside down, all this sort of stuff. And the car has to be yellow.” I think the producer found a guy on Craigslist who had an old Camry and was like, “I just need to get rid of it.”

Obviously, we didn’t articulate to this gentleman that we were going to destroy it. So we gave the boys baseball bats. They smashed it up—it was real glass. I think the co-director Joe sliced his finger on one. I still have the Vans slip-on that has a drop of blood on it. The gas can was just water. It was all super safe in terms of the pyrotechnics. That last shot where it’s on fire was all created in After Effects. Our production designer lit fire on the ground around them, and then in the computer, I put it all over the car. That’s one of my favorite scenes that I’ve worked on just because it was so wild and out there and fun.

The other shot that really stands out is the image of Awsten framed against the floral backdrop. How did you develop the rest of the video?

The name of the DP on that was Matt [Hoodhood]. The production designer, her name is Skye [Prey]. She found all these tapes and stuff. We really went in on that video because we wanted to make the production value as high as possible. She was going all over town finding VHS tapes. It’s really funny because she painted the car. If you look really close, it’s her hand that comes through the pillow in the first half. If you pause it, you can see that some of the paint is on her hand from painting the car that day.

Then we shot the bathroom scene. That was DE’WAYNE’s shower, and we were like, “Dude, you should get in the shower and just soak yourself in water.” The narrative isn’t necessarily concrete, but in the Waterparks universe, it all has meaning. The wonder of working with different musicians is for one video, you’re a part of their creativity. You’re part of their world that they’ve created.

Shifting gears a bit, I wanted to ask you about your video for Herizen’s “Troublemaker.” It’s a fun but simple video compared to some of your other projects. How did that project come about, and what were you going for?

That was just through the internet. Their manager reached out to me and was like, “We’d love to work with you.” It’s another thing where they have an idea, [and it’s like], “How can we figure out how to do this idea with the budget?” I’m not the type of person who’s doing these low-budget videos all the time. With people I’m friends with or I believe in the project, it’s one thing. Because it’s really easy to get burned out.

[Herizen Guardiola] is an actor in conjunction with being a musician. Her on-camera presence was amazing, and just in general, she’s a very strong, powerful personality. She knew exactly how she wanted to look in this video and everything. So basically, the “Troublemaker” concept was just doing punky shit in a pool, just a day of hanging out with skaters and our homies.

The last video I wanted to ask you about is Halo Boy’s “Fame.” It has that great throwback industrial atmosphere. What was the goal with that project?

For that video, we did it 4:3, which is a square format, and it was super inspired by the ’90s. We did a thing where the song’s playing at 50%. There’s these five-and-a-half minute long takes where he’s singing in slow motion, but then when you do the speed ramp in post, it’s like he’s twitching and going crazy. We did a lot of super-high key lighting, [and] we had an egg chair, which is this wild chair that I think was in Men In Black. Halo Boy has these black sclera contacts. We filmed in night vision, and then I took a bunch of photos, and we just had a field day.