10 rockers from the ‘50s who influenced rock 'n' roll, punk and more

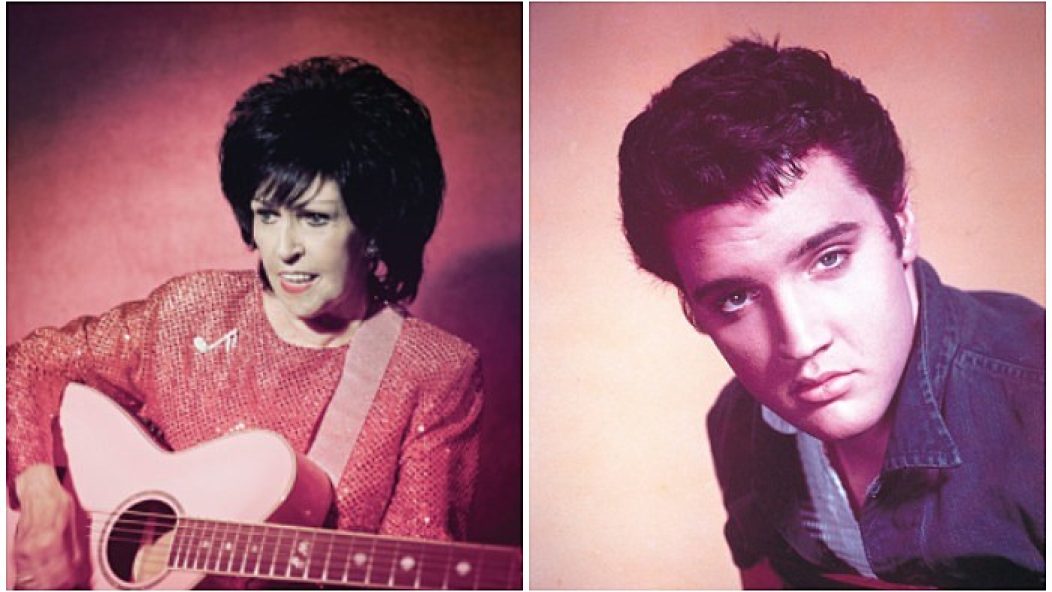

Elvis Presley portrayed by actor Michael St. Gerard performing “Baby Let’s Play House” in 1955 in the 1990 ABC TV series “Elvis”:

Rockabilly is the original punk rock, from back in the dawn of rock ‘n’ roll in the 1950s. Nothing is more rebellious and life-affirming than some greasy hillbilly gittin’ real, real gone on a fistfull of pills and moonshine in Sam Phillips’ Sun Records echo chamber. It originated the impulse to strap a rocket-engine to basic three-chord music and flash some serious attitude. And nothing terrified the good Eisenhower-voting parents of the era than the sight of some skinny country boy shakin’ on TV, overly Brylcreemed hair hanging in his eyes and dolled up in a pink-and-black suit, mumbling about what he wanted to do to mah bay-beh over a loud, thumping mashup of honky-tonk country and gutbucket blues. To his left, some clown is jumping around atop a doghouse bass. To his right, an utterly impassive statue of a man reels off flashy runs on an over-amped electric guitar. To those good gray-flanneled parents of the age, this was sinful. And their daughters were screaming at these twangy hoodlums!

Read more: Gang Of Four on their political roots, new box set ‘‘77-’81’ and more

Rockabilly’s influence on punk is incalculable, from Richard Hell writing in his memoir I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp of tapping into its primal energy to the Sex Pistols covering Eddie Cochran classics. The Clash especially flashed a strong rockabilly yen: aping the first Elvis Presley album’s graphics for London Calling; adopting greasy ducktail haircuts and cat clothes; covering Vince Taylor’s “Brand New Cadillac,” Britain’s first authentic stab at rockabilly glory. Then there was the Cramps’ obvious retrofit of rockabilly for the ‘70s punk era. Rebel rock will always look back at rebel rock past for inspiration.

As with any cultural tumult, rockabilly had its precedents. Most immediate were the “hillbilly” boogie records of the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, especially Arthur Smith’s “Guitar Boogie” and Hank Williams’ “Move It On Over.” Then there were the raw blues artists Phillips was recording at Sun in the early ‘50s—Howlin’ Wolf, Junior Parker, James Cotton. Phillips kept musing aloud that if he could find a white musician who played with the soulfulness and conviction of the blues performers he’d been recording, he could make a million dollars. Contemporaneous with rockabilly’s rise was the hard-driving R&B DJ Alan Freed sold to white teens as rock ‘n’ roll—pounding eighth-note raunch by Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Bo Diddley. African American rock ‘n’ rollers and future greasy country boys benefitted as much as Phillips when the embodiment of his dreams of a white blues singer walked through Sun’s front door in 1953.

Listen to our custom Spotify playlist, “Go, Cat, Go!”: Rockabilly, 1955-1959, as you read:

Elvis Presley

The effect of Elvis Aron Presley of Tupelo, Mississippi, cannot be overestimated, though many nowadays try to underestimate it. He didn’t invent rock ‘n’ roll anymore than the Sex Pistols invented punk. There’s always a figure who comes along with enough charisma and raw talent who knocks down doors, becoming any musical or cultural revolution’s definitive exponent, the one who clears a path for the rest to walk through. This was Elvis Presley. His talent was so incandescent, it could not be denied. He was truly a once-in-a-lifetime phenomenon whose likes will not be seen again.

If anything, he invented rockabilly the day at Sun Records’ studios that he added a jumped-up country twang to fifth-string blues artist Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup‘s “That’s All Right,” then a cranked-out R&B rhythm to bluegrass godhead Bill Monroe’s “Blue Moon Of Kentucky.” He achieved the same alchemy across four more yellow label Sun 45s, in the company of slap bassist Bill Black and whizbang guitarist Scotty Moore: “Good Rockin’ Tonight” served notice that something really hot would now take over the nation’s jukeboxes—“We gonna rock all our blues away!” “Baby, Let’s Play House” warned an errant lover that she was getting an inordinately swollen ego: “You may have a pink Cadillac, but don’t you be nobody’s fool.”

Read more: Turnstile connects with friends Will Yip and Atiba Jefferson

His sound got tougher, rawer, ballsier, dripping with Phillips’ tape echo, gaining extra drive by the time the trio added a drummer for the locomotive “Mystery Train.” Meanwhile, the band barnstormed the South, displaying Presley’s matinee idol looks and burlesque artist stage presence to hundreds of screaming teenage girls—this was raw sexuality on public display for the first time. Those country boys not jealous over their girlfriends’ swooning over this punk took notes and considered trying to get Phillips’ attention themselves…

A veteran carnival barker named Col. Tom Parker signed Presley to a management contract in 1955. In turn, he waved his boy before several major labels, RCA taking the honors in gold-handshaking Sun’s golden goose away. Next came television, movies and a simultaneous hardening and popifying of his sound. Such records as “Hound Dog” and “Jailhouse Rock” are as punk as they come—you can hear the Ramones 20 years early in “Hound Dog”’s machine-gun rumba rhythms and nasty attitude. Presley became a millionaire by the time he turned 22, history’s first rock star, so big he was known internationally by his first name. But the Hillbilly Cat, as he was billed in 1955, was long gone.

Carl Perkins

Carl Perkins was the first of those country boys to show up at Sun after hearing Presley’s first record on the radio in 1954. He and brothers Clayton and Jay Perkins had been playing honky tonk in and around Jackson, Tennessee, with their own mix of hardcore country tunes and the blues guitar passages Carl learned from a Black sharecropper named “Uncle John” Westbrook during his poverty-stricken childhood. One of the tunes to which the trio applied their country boogie chops was “Blue Moon Of Kentucky.” Phillips liked what he heard, though Carl’s first single “Movie Magg” was much twangier than any of Presley’s releases thus far.

Haunted by hearing a teen accosting his date for scuffing his shoes on the dance floor during a 1955 road date, Carl wrote “Blue Suede Shoes” on the back of a paper sack. Sun suddenly had its next star, with Presley moving into his 1956 ascendance. “Blue Suede Shoes” sold a million copies and was even covered by Presley himself. A car accident en route to a New York TV appearance derailed Carl’s career instantly. He continued to cut wild, untamed rockabilly ravers such as “Matchbox” and “Put Your Cat Clothes On.” But the momentum behind “Blue Suede Shoes” had dissipated. Still, Carl worked until his 1998 death, his dedication to hardcore bopping undiluted by runaway fame a la Presley.

Johnny Cash

In certain quarters, Johnny Cash’s reputation as the rebel king of rock ‘n’ roll exceeds Presley’s. Myths have grown since the Man In Black’s 2003 death, perhaps stoked by the Hollywood biopic Walk The Line. But Cash was a post-Presley Sun Records rockabilly, one of the label’s stars from June 1955 debut single “Hey Porter” b/w “Cry! Cry! Cry!” onward. He had a dark, brooding intensity all his own, perhaps exacerbated by the amphetamines he gobbled by the handful driving from one-nighter to one-nighter, hundreds of miles apart. The sound developed with his Tennessee Three bandmates Marshall Grant on bass and the dour Luther Perkins on guitar was lean and spare, devoid of fat. And there was an earthiness to hard-driving classics such as “I Walk The Line” and “Big River” that no other rockabilly possessed. Then there’s the case of the harder-than-hard “Folsom Prison Blues”: “But I shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die.” Patti Page wondering “How Much Is That Doggie In The Window,” this ain’t.

Gene Vincent

Capitol Records, like every other American record label in 1956, were blindstruck by the massive success of “Heartbreak Hotel.” They needed their own Elvis. They got a lot more than they when they inked Norfolk, Virginia’s Gene Vincent, who had his own massive success with the immortal “Be-Bop-A-Lula” in 1956. There was enough Elvis in his hiccupping baritone that the record fooled Gladys Presley, who congratulated her son after hearing Vincent’s record on Memphis radio. But Vincent’s hoodlum veneer flashed more authenticity—his heavy-panting that he was “lookin’ for a woman with a one-track mind” across B-side “Woman Love” left no listener uncertain what he was after.

He looked greasier, limped heavily due to a gimp leg that never healed from a 1955 motorcycle accident, had a completely unhinged stage act that made Presley look like a choirboy and employed an impressive band in the Blue Caps, especially nimble-fingered guitarist Cliff Gallup. Vincent was so scary, he never achieved another U.S. hit. He amped up his drinking across endless European tours, where he exaggerated his limp and played up his rebel image in head-to-toe back leather. He drank himself to death in 1971, barely remembered at the age of 36.

Wanda Jackson

The pride of Oklahoma City, Wanda Jackson had been singing straight country since her teen years in the early ‘50s. She was encouraged by Presley to switch to rock ‘n’ roll when she opened a series of his 1955 road dates. When she made the switch in 1956, no one could have expected the white-hot intensity she’d create. Her rockabilly work was utterly pioneering, sticking out in what was otherwise a sausage party in an echo chamber. Her sexuality was as intense as Presley’s, and her voice was an awesome instrument, capable of a thrilling growl as easily as a soothing croon. She turned Presley’s own “Let’s Have A Party” into a raucous war whoop, generated blasting atomic heat on “Fujiyama Mama” and managed to make the Drifters’ “Riot In Cell Block Number Nine” sound genuinely dangerous. With blistering guitar work from Roy Clark, Jackson was the major female rockabilly artist, as historically important as Janis Joplin or Joan Jett.

Johnny Burnette And The Rock ‘n’ Roll Trio

“Git along!” growls the greasy Memphian. “Sweet little woman, git along!” The singer’s howling through a thick cloud of echo, as the bass player slaps at his upright bull-fiddle like he’s spanking an errant child. The guitarist, meanwhile, is pulling metallic shards of serrated-edged tone out of the air like molotov cocktails—one of history’s first recorded instances of distorted electric guitar. No, this ain’t Elvis, Scotty and Bill at Sun—this is Johnny Burnette And The Rock ‘N’ Roll Trio at Bradley’s Barn in Nashville, usually given to more staid country fare, attaching a helicopter motor to bluesman Tiny Bradshaw’s “The Train Kept A Rollin’.”

Burnette, bassist brother Dorsey and distorto-Telecaster man Paul Burlison all grew up in the same Memphis housing projects as Presley, the latter even working with him at Crown Electric in his truck driving days. They marinated in the same swamp of country, blues and R&B that he did, perhaps playing it rawer than their neighbor. Eventually, the Burnette brothers broke up the act and moved to L.A., where they wrote hit songs for teenage TV rockabilly Ricky Nelson. Johnny became a teen idol himself in the early ‘60s with such considerably more tame fare as “Dreamin’” and “You’re Sixteen.” He was killed in a 1964 boat accident.

Jerry Lee Lewis

The fourth of Sun Records’ “Million Dollar Quartet” was possibly its most talented. Ferriday, Louisiana’s Jerry Lee Lewis was an untutored boogie-woogie piano genius who never took a lesson in his life, who abused every keyboard he sat before with all the abandon of a rampaging horde of visigoths and sang with a leer that left no doubt what was shaking in the song that made him a star. For two years, every song he touched was pure gold, supercharged boogie-woogie rock ‘n’ roll that terrified mom and pop more than that nasty Elvis and thrilled every teenage ear who heard him.

“Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On,” “Great Balls Of Fire,” “Breathless,” “High School Confidential”—an unparalleled string of solid senders, full of unschooled artistry and demonic energy that simultaneously scared and thrilled all who heard him. For a moment, Lewis was poised to snatch the rock ‘n’ roll crown from Presley’s head while he went in the Army. But the man lived wilder than any other early rocker—his drink and pill intake was legendary, and marrying a distant cousin in her early teens did his career no favors. Yet still active at age 85, the Killer is indeed the last man standing out of the first generation of rockers.

Eddie Cochran

Imagine Presley if he’d written his own songs and produced his own records. This was likely director Frank Tashlin’s idea when he cast Eddie Cochran to be a sort of Elvis stand-in in the first credible rock ‘n’ roll film, The Girl Can’t Help It. Cochran’s appearance revving up his own “Twenty Flight Rock” is like a fever dream version of Presley on The Ed Sullivan Show. But Cochran was a skilled lead guitarist whose riffs were being cribbed by punk bands 20 years later. His tunes such as the classic “Summertime Blues,” “C’mon Everybody” (covered by the Sex Pistols) and “Somethin’ Else” (covered by the Pistols and the New York Dolls) captured teen frustration better than any other ‘50s rocker this side of Chuck Berry. He was another pioneer of guitar distortion and an early experimenter with multitrack recording. He burned brightly and briefly, dying at age 21 in a taxi accident in England that also worsened friend and tourmate Vincent’s long-standing leg injury.

Link Wray

Link Wray was a jobbing rock ‘n’ roll guitarist in the Washington, D.C. area who had to improvise a “stroll” onstage at a Fredericksburg, Virginia sock hop in 1958. Recorded by popular demand, it was bolstered by the distorted tone Wray achieved by slashing his amp’s speakers, then utilizing two-finger chords that later came to be called “power chords.” “Rumble” became an instant sensation, despite receiving blanket bans at many radio stations for “inspiring juvenile delinquency”—an instrumental. In the process, Wray created the classic sound of both punk and heavy metal, riding it through a career that lasted his death at age 76 in 2005.

Ricky Nelson

Ricky Nelson gets a bad rap as a prefab teen idol, likely because he grew up in front of the American public as the wise-cracking youngest son on the long-running TV series The Adventures Of Ozzie And Harriet. But Nelson’s records were some of the most authentic, hard-driving rockabilly records to come from California, even if father Ozzie Nelson cannily used the TV series to promote his son the rocker as a clean-cut Elvis alternative. Which was fair enough, considering Presley and other Sun Records artists were Nelson’s initial inspirations.

But he had a crackerjack band of teenage Louisiana expats who’d previously backed such artists as Dale Hawkins and Bob Luman, centered around the bent-string Telecaster wizardry of James Burton, lynchpin of Presley’s ‘70s band. He also had ace rockabilly writers such as Johnny and Dorsey Burnette penning strong material that produced hit after hit—“Believe What You Say,” “Waitin’ In School,” “Stood Up.” When he borrowed rockabilly standards such as “My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It,” he frequently improved on them, creating immaculately raucous records. All these factors made him Presley’s only serious rival commercially—Nelson had 30 Top 40 hits between 1957 and 1962, compared to Presley’s 53. It’s perhaps time to finally reevaluate Nelson and consider him a peer of fellow California rockabilly Cochran.